Read

Designed Equity: Reflection on Youth-focused Game Jam in South Central...

Educator innovator Antero Garcia shares his observations about a game jam in LA and some...

Connected learning scholar Mimi Ito explores lessons learned from a successful long-distance collaboration to create innovative STEM learning experiences for elementary students.

A little over a year ago, Mahad Ibrahim reached out to me about Connected Camps, an organization I’m leading with Katie Salen that offers online learning programs and mentorship in Minecraft. Mahad and I go way back. Nearly a decade ago, Mahad had been part of the Digital Youth Project that I co-led, when he was a Ph.D. student at the UC Berkeley iSchool. More recently, Mahad had teamed up with entrepreneur and escape room designer Alexis Santos in launching Mind Foundry, an organization providing STEM learning experiences to underserved kids in the Twin Cities. Would we be interested in running an after school program together?

After a mind meld between teams, we started to put meat on the bones. We ran our first pilot last spring with 49 elementary school kids at St. Paul City School. Connected Camp counselors beamed into the school via video chat and Minecraft, and worked together with local facilitators to deliver an after school game design program. By working closely with Mind Foundry staff who worked as on-site mentors, Connected Camps counselors were able to run our design programs in a hybrid format. The program is expanding to 100 kids and a more ambitious and lengthy set of offerings.

The partnership and program design is complex, involving Mind Foundry, Connected Camps, the school, and of course the kids and families we serve. On top of that, delivering high-quality, innovative, project-based STEM programs in a low-income public elementary school is a hefty challenge. Despite these challenges, co-developing and running the program has been a pleasure, and we seem on track for a successful expansion. Here’s five lessons about what’s made the collaboration succeed: trust, diversity, breaking rules, co-learning, and shared purpose.

One of the critical intangibles undergirding successful innovation is trust, particularly when it involves crossing traditional boundaries between organizations and settings. The personal history Mahad and I shared was a starting point, but mutual trust extended well beyond our relationship.

The Mind Foundry and Connected Camps teams quickly learned to stay in sync through various online channels. I asked Mohamed Yousif, one of the on-site Mind Foundry staff, how it was working with a virtual counselor. He explains, “We work very well together because the lines of communication are open. We’re on Slack. We understand that we are working toward a common goal. We troubleshoot in real time.” Alexis describes this as a “startup style approach.” The fact that both Mind Foundry and Connected Camps are innovation-oriented startups helped establish trust early, and open dialog has kept it chugging along.

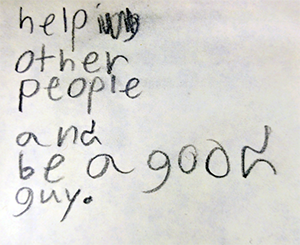

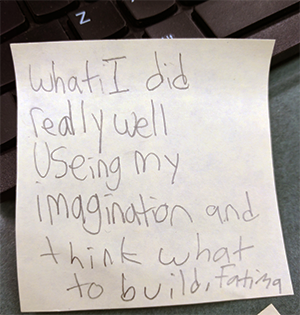

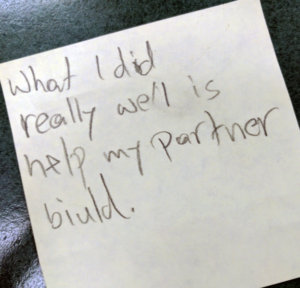

Student reflection

This open communication extends to school staff as well. The decision to launch the pilot at St. Paul’s happened quickly, and the Mind Foundry team had only a couple weeks to prepare. Mahad was in ongoing discussion with Justin Tiarks, the school principal “We were up front about what we can and can’t do.” He says he runs everything by Justin, but “he trusts us to deal with it and the logistics.” This trust is built on this open dialog. “It’s not that there weren’t hiccups, but we are very communicative and keep iterating.”

This spirit of give and take extends to the kids as well. One student reflects after the first week on what they did well—“help other people and be a good guy.”

The trust that undergirds the collaboration is built on mutual respect for what varied parties bring to the table. Early on at Connected Camps, we realized that we didn’t have the capacity to both build online programs and be at the front lines of managing relationships with schools, libraries, and community-based organizations. We sharpened our focus to specialized STEM programs and developing a network of virtual counselors, and began partnering with groups who were working locally, and could be at the front lines of high-touch relationships with local educators, organizations, and kids. For example, we’ve been working for several years with Building Blocks for Kids Collaborative in offering a Minecraft summer camp to kids in Richmond, California.

When Mahad approached us about working with Mind Foundry, we recognized a good fit, because both sides needed the expertise and capacity that the partner brought to the table. Alexis notes that “managing the logistics at the school is a full-time project in and of itself. Having Connected Camps as a partner let us focus on our strengths, and we didn’t have to stress about creating the program itself.”

This principle of embracing diversity in expertise and perspectives extends beyond Mind Foundry’s partnership with Connected Camps. Front line facilitators were recruited to reflect the diversity of the student body, who are 80% kids of color. Mahad says that the school staff, parents, and kids all commented on this. One student mentioned that he had never had a teacher who is Muslim before.

The programs themselves are designed to stress collaboration. Mohamed sees learning how to collaborate as one of the most important outcomes. “Eventually they start finding out, if they work with a person, and build through a shared goal, not only is it faster and more efficient, but they are learning what others prefer and how they like to work. They learn to compromise a bit.”

Mohamed, Alexis, and Mahad all described how certain non-traditional learning experiences were a key reference point for them in their work at Mind Foundry. Mohamed built his own interdisciplinary major at University of Minnesota, which integrated design and marketing. Alexis was able to create his own path at the New College of Florida where he was able to marry his interests in anthropology and technology. Mahad experienced this kind of more self-directed learning approach in graduate school at UC Berkeley. He specifically reached out to Alexis because “he had this hybrid background and he learned almost entirely by experimenting and trying things.”

Breaking down boundaries, experimenting, and tinkering — this orientation is what makes for innovative and iterative development in both program design and for the kids. Minecraft is a great platform for this. Alexis notes that the use of Minecraft was one of the biggest things that popped for both kids and the school-based educators. “The kids would ask in hushed tones, ‘Are we really going to play Minecraft?’ The first day, it was pretty rowdy.” A big part of the excitement was that they were breaking what they thought were the rules of school — playing video games, messing around with their peers, and having fun.

Mohamed notes, “education shouldn’t be a chore, it should be an adventure.”

Mohamed notes that his biggest challenge when he started in the spring pilot was that “I’m not a teacher.” He was also new to Minecraft.

At first, I struggled with the teaching and classroom management aspects, but in the end, it worked to my advantage. Because I didn’t have the teacher qualities, I was able to connect with the children a lot more. I didn’t know Minecraft. I was listening because I wanted to learn what to do. I wasn’t seen as a teacher. I was treating them like my nephews. Now when they see me, it’s all hugs.

Like Mohamed, Alexis and Mahad were also new to working with a school in this way, but were bringing in a set of educational values, and expertise in tech making that animated the program and brought unique value to the school. Alexis described how the first meeting with the school when he was in a room with other after school program providers was “pretty intimidating.” But it became clear that Mind Foundry’s commitment to serving the students over the long haul, and to learning and iterating like a startup really made them stand out.

Our team at Connected Camps also finds the startup mentality of constant adaptation and real world learning is a source of ongoing motivation. And, like Mind Foundry, we apply this to how we design experiences for kids. The excitement is that all of us are imagining new worlds and figuring out together how we can build them.

The final important lesson from this collaboration has been just how important shared vision and values have been. When speaking to the Mind Foundry team, it was clear that they had arrived at what I consider the core principles of connected learning, each through their own unique experiences. It is the combination of experiencing connected learning themselves, and the shared values of equity that hold the team together, and make Mind Foundry a strong fit with Connected Camps.

Mahad is of Somali descent, but hadn’t been deeply connected to a Somali community until he moved to Minneapolis. He started tutoring kids as a volunteer effort, and quickly realized that what kids really needed and wanted was authentic learning experiences like what he had experienced in graduate school. He eventually reached out to Alexis, who he new had a similar orientation to learning and making.

That is the genesis of Mind Foundry. I didn’t want to create a thing that was only for people who can afford it. These techniques should be available widely. I wanted to target kids who didn’t have access to it. I only had this type of thing until I got to graduate school. Why can’t we take similar approaches to younger groups? A lot of these youth won’t get this opportunity. So let’s get real.

By Mimi Ito

Originally Posted at DML Central

Photo/ Connected Camps